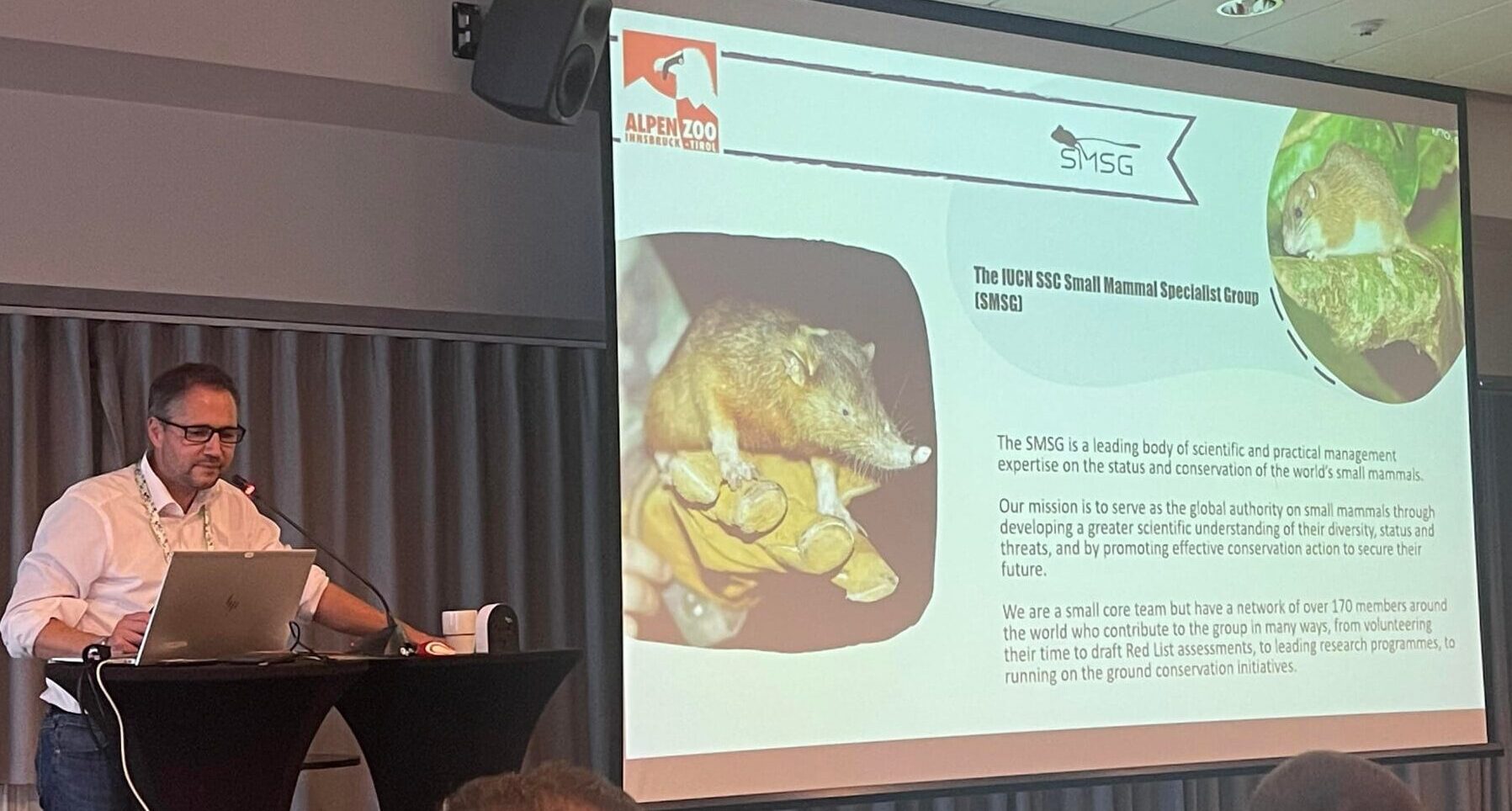

Alpenzoo (Austria) is the 19th conservation organisation to establish a Centre for Species Survival in collaboration with the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC), the world’s largest volunteer conservation-science network.

Five of the nineteen Centres recognised globally by the SSC are based in Europe. Alpenzoo is proud to announce the establishment of a new Centre for Species Survival, which will significantly enhance their commitment to the conservation of small mammal taxa.

Centres for Species Survival are partnerships between conservation organisations and the SSC – a Commission made up of more than 10,000 species conservation experts worldwide. Centres are hosted by leading zoological, botanical and aquarium conservation organizations that are actively focused on key species or specific geographical regions.

Within this collaboration, Alpenzoo will be teaming up with the IUCN SSC Small Mammal Specialist Group (SMSG) to assess risk of extinction within this animal group and help speed up the planning and implementation of conservation action. The first step will be the establishment of a Programme Officer based at Alpenzoo, working remotely within the Specialist Group.

Co-Chair Ros Kennerley

“The IUCN SSC Small Mammal Specialist Group is delighted to be part of this exciting new partnership, which aims to bolster conservation efforts for the world’s 3,200+ small mammals. We look forward to growing our team with Alpenzoo and working with them to assess species for both the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and Green Status and support conservation planning for species and multi-species planning in key regions.

Having a dedicated member of staff based at Alpenzoo will make a huge difference to what the SMSG can achieve for small mammals, which are generally under-researched and over-looked in terms of conservation funding and activities. It is brilliant to have Alpenzoo on board and we hope to see other institutions within the zoo community also step up to assist small mammal conservation.”

Dr Ros Kennerley, Co-Chair of the IUCN SSC Small Mammal Specialist Group, based at Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust.

The SMSG represents a global network of scientists and conservationists who share a passion for the world’s often overlooked and under-studied rodents, shrews, moles, solenodons, hedgehogs and treeshrews. The Group serves as the Red List Authority for these taxa, but also works to promote conservation actions on the ground and develop strategies to enable more effective projects for small mammals. Alpenzoo has long been interested in small mammal work, having developed a breeding programme for the Bavarian pine vole (Microtus bavaricus). The vole is now being transferred to other zoos, with a few specimens also being released into the wild for the first time this year.

“Our new Centre for Species Survival in collaboration with the SSC marks a significant milestone, as it is an honor to become the 19th zoo worldwide to initiate such a vital program. CSS Alpenzoo will play a crucial role in providing scientific insights, assessing extinction risk, and expediting the planning and implementation of conservation action. Our mission is to ensure the survival of highly threatened species across the globe, and we are already witnessing promising outcomes. For instance, our conservation project for the Bavarian pine vole has achieved groundbreaking success taking place right here at the Alpenzoo.

We are committed to continuing our efforts to protect and preserve biodiversity. This new Centre will enable us to contribute even more effectively to global conservation initiatives, ensuring a brighter future for many threatened species.”

Dr André Stadler, Alpenzoo Director.

Alpenzoo is unique in that it exclusively houses Alpine species native to the region. Visitors are treated to stunning views of Innsbruck and the surrounding mountains while exploring a habitat that includes over 2,000 individuals across 150 animal species typical of the Alps. As the only zoo globally dedicated to Alpine wildlife, it has achieved considerable success. The zoo is actively involved in reintroduction initiatives for various species, including wild cats (Felis silvestris), bearded vultures (Gypaetus barbatus), black vultures (Aegypius monachus), European pond turtles (Emys orbicularis), and Northern Bald Ibis (Geronticus eremita).. Notably, it has conducted annual ibex (Capra ibex) releases for over 20 years and is planning on releasing a variety of different animals in the future. Through the new Centre for Species Survival, Alpenzoo will further increase their focus on small mammal taxa across a range of outputs, from coordinating global-level Red List and Green Status assessments, to promoting small mammal work within the zoo itself.

“We are excited to have Alpen Zoo join the global network of Center for Species Survival partnerships which now spans 13 countries and 6 continents. Together these leading conservation institutions have hired almost 50 highly-qualified staff working in support of priority species conservation science and action. Through joint efforts like these we can secure a thriving future for the species we share this planet with.”

Dr Kira Mileham, IUCN SSC Strategic Partnership Director.

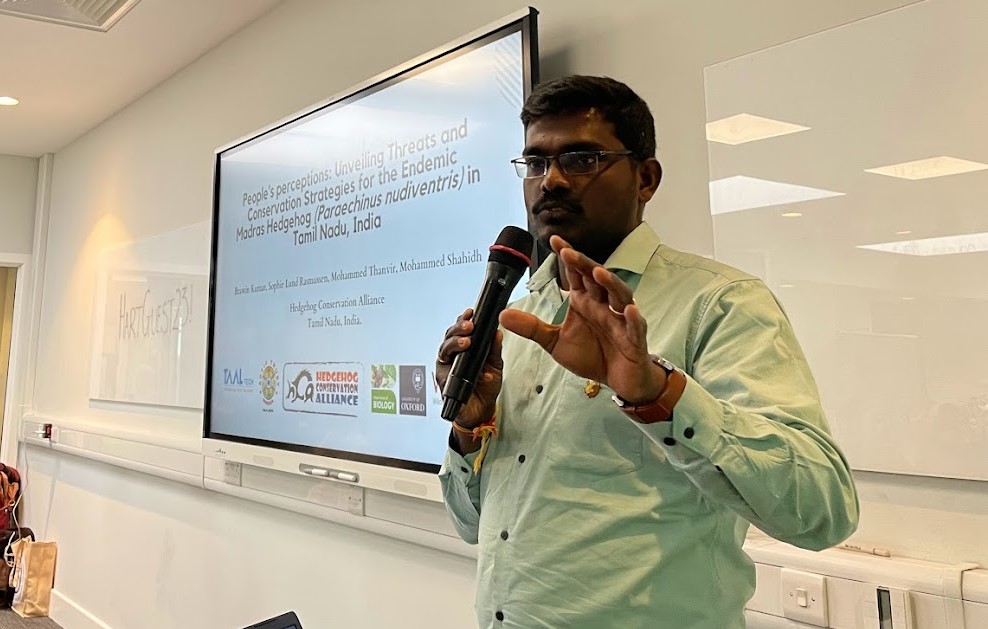

Official launch of the Alpenzoo CSS. Photo credit: Thomas Steinlechner

Joining this team is immensely exciting for me as it presents a chance to delve into the process of conducting assessments firsthand. It’s the perfect opportunity to apply the new framework I’ve learned about, which aims to quantify measures of species recovery and conservation success. As an early career conservation biologist, I’m particularly drawn to the Green Status’s focus on understanding how past conservation efforts have impacted species recovery and how current and future actions can contribute to their conservation with a comprehensive and ecologically functional approach. This opportunity will also give me the chance to interact with species specialists and learn about their conservation work on new species for me, which is really exciting!

Joining this team is immensely exciting for me as it presents a chance to delve into the process of conducting assessments firsthand. It’s the perfect opportunity to apply the new framework I’ve learned about, which aims to quantify measures of species recovery and conservation success. As an early career conservation biologist, I’m particularly drawn to the Green Status’s focus on understanding how past conservation efforts have impacted species recovery and how current and future actions can contribute to their conservation with a comprehensive and ecologically functional approach. This opportunity will also give me the chance to interact with species specialists and learn about their conservation work on new species for me, which is really exciting!

The findings

The findings

Recent Comments