On April 27, 2025 a contingent of three Ukrainian scientists from the Kyiv Zoo arrived in San Diego for a study tour with the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. The Ukrainians have been involved in the conservation breeding and reintroduction of the now Critically Endangered European Hamster (Cricetus cricetus) into the steppe region of Ukraine. The project is led by Dr. Mikhail Rusin of the Kyiv Zoo, also a SMSG member. As a supporter of this program, Zoo New England (ZNE) requested and received a grant from the foundation Trust for Mutual Understanding to provide the scientists from this war-torn country a chance to learn from one of the world’s best captive breeding and reintroduction team.

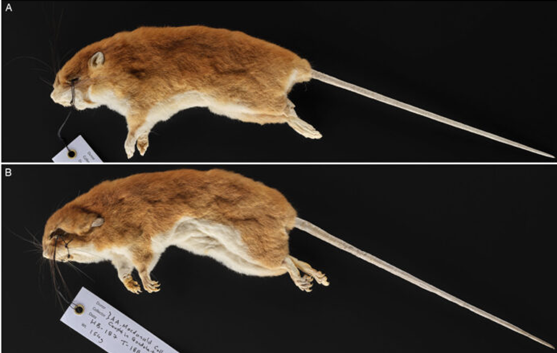

The Ukrainian team was supported by Peter Zahler of ZNE, also a SMSG member, and hosted by Dr. Debra Shier, who is the Alliance’s Brown Endowed Associate Director of Recovery Ecology. Dr. Shier and her group work on a number of small mammal translocations, including a very successful Stephen’s Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys stephensi) program and the program the Ukrainians observed during their visit, on the Pacific Pocket Mouse (Perognathus longimembris pacificus). These tiny mice, the smallest in North America, were thought extinct until a small population was discovered in the 1990s. They currently can be found in only three sites, and probably still number only about 200 animals along the coast of southern California.

Over the next nine days, the Ukrainians were provided with both presentations and hands-on opportunities to learn cutting-edge methods in husbandry, breeding decisions, hormone trials, genetic studies, health assessments, and data management protocols. They also learned about the complex decision-making that goes into identifying potential release sites. Finally, they learned about behavioural competency conditioning for the mice to prepare them for life in the wild, including predator avoidance, shelter use, and foraging.

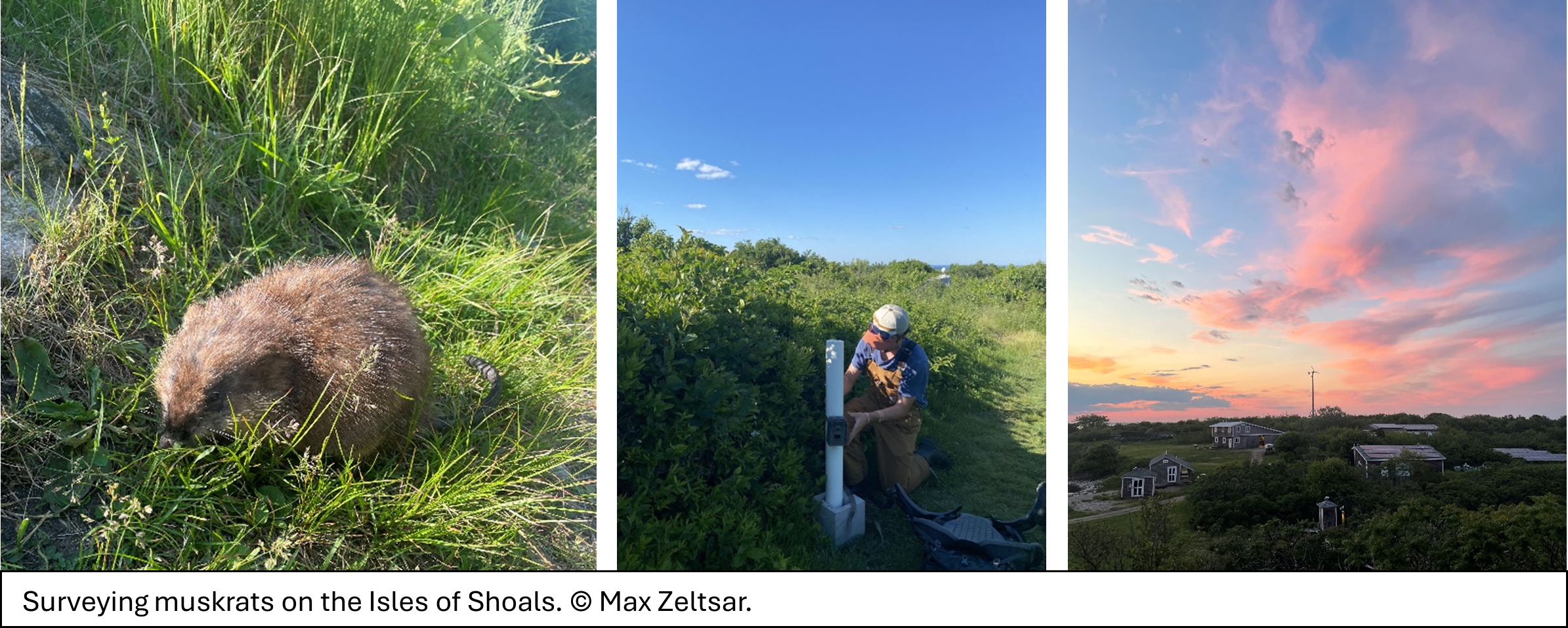

The team also went into the field to help with a “soft release” of 50 Pacific pocket mice into small cages out in the coastal scrub, helped with vegetation surveys, and finally went out to remove the “soft release” cages and free what might well be 20% of the wild population of this highly threatened small mammal. They have since returned to Ukraine where they will attempt to put what they’ve learned into practice for the European hamster initiative.

Author: Peter Zahler, Director of Field Conservation at ZNE, SMSG member

Recent Comments