We have a challenge. A rather large one.

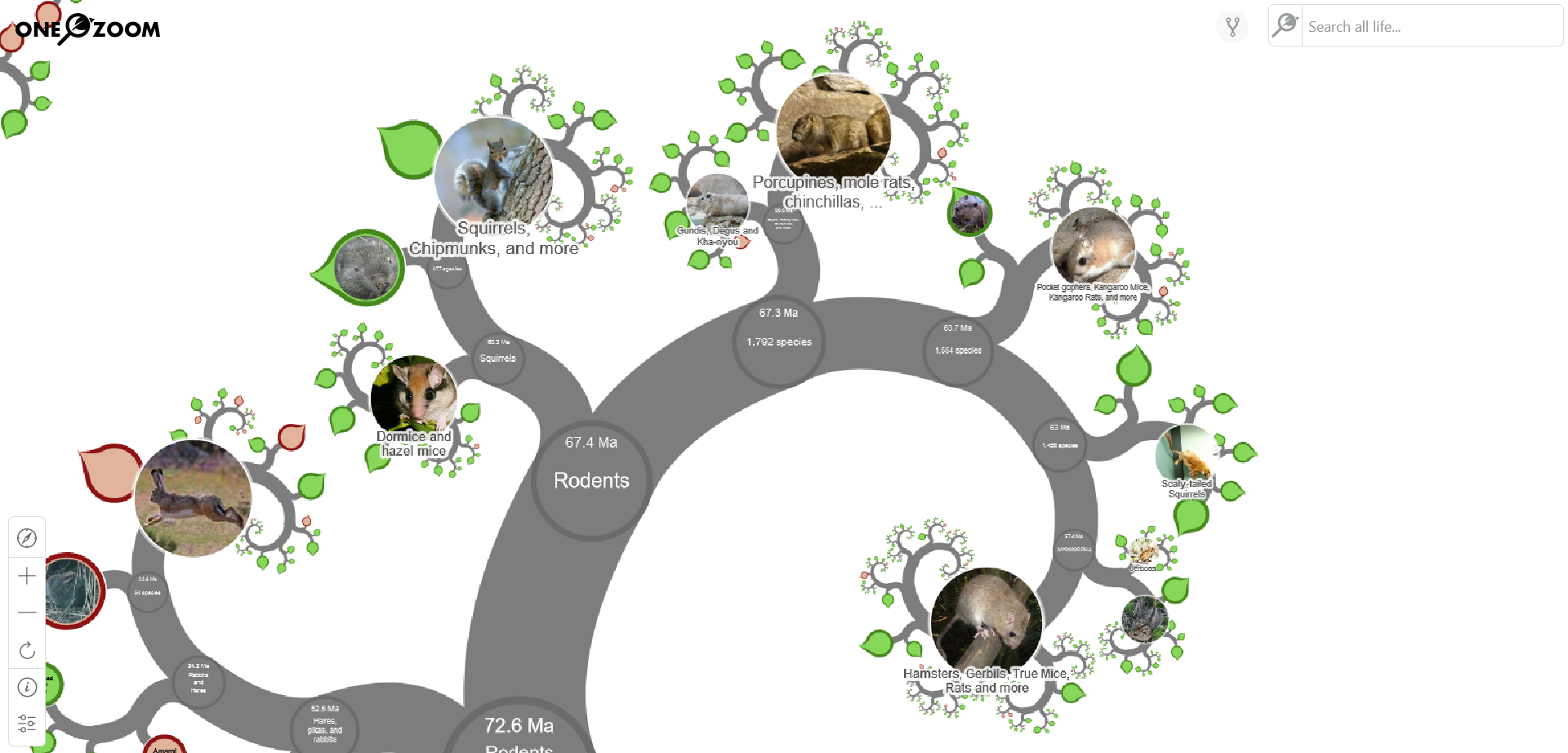

Along with the other mammal Specialist groups, the SMSG conducts Red List assessments of all its species. These assessments involve gathering up-to-date taxonomic and ecological information for species, the threats they face and the conservation actions they require. Not too challenging for a handful of species – our problem of course is that there are well over 3200 small mammals!

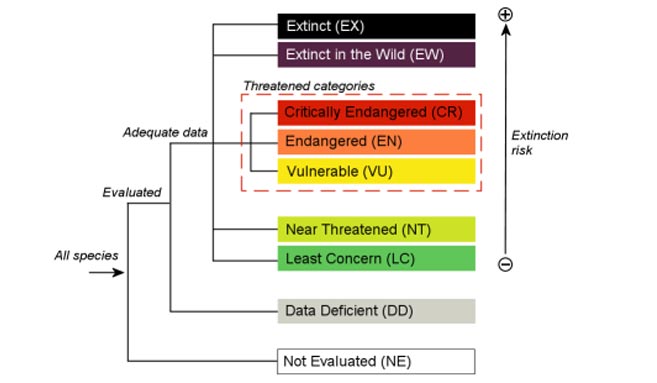

If there isn’t enough ecological information to properly assess their extinction risk or if there is taxonomic uncertainty, then a species will be classified as Data Deficient. The group has around 450 poorly known species which are currently considered Data Deficient.

The SMSG works with the Global Mammal Assessment Team at Sapienza University, Rome, to deliver this huge project. Assessments are usually drafted by our team, often with the expertise of our members. The assessments are then reviewed by independent experts and then sent to the IUCN Red List Unit for final checks before being published on the IUCN Red List website. Along with all the other Red List assessments of mammals, amphibians, fungi, plants and so on, they will form a number of global biodiversity indicators which allow progress towards global environmental and development goals to be tracked.

In 2022, the SMSG took the decision to use the Mammal Diversity Database taxonomy for all future Red List assessments. We are in the process of working with the GMA to make changes to the database and following this we will begin creating new assessments where necessary and reassessing species that are affected.

If you would like to provide your knowledge of certain species to help draft species accounts then please get in contact with the group.