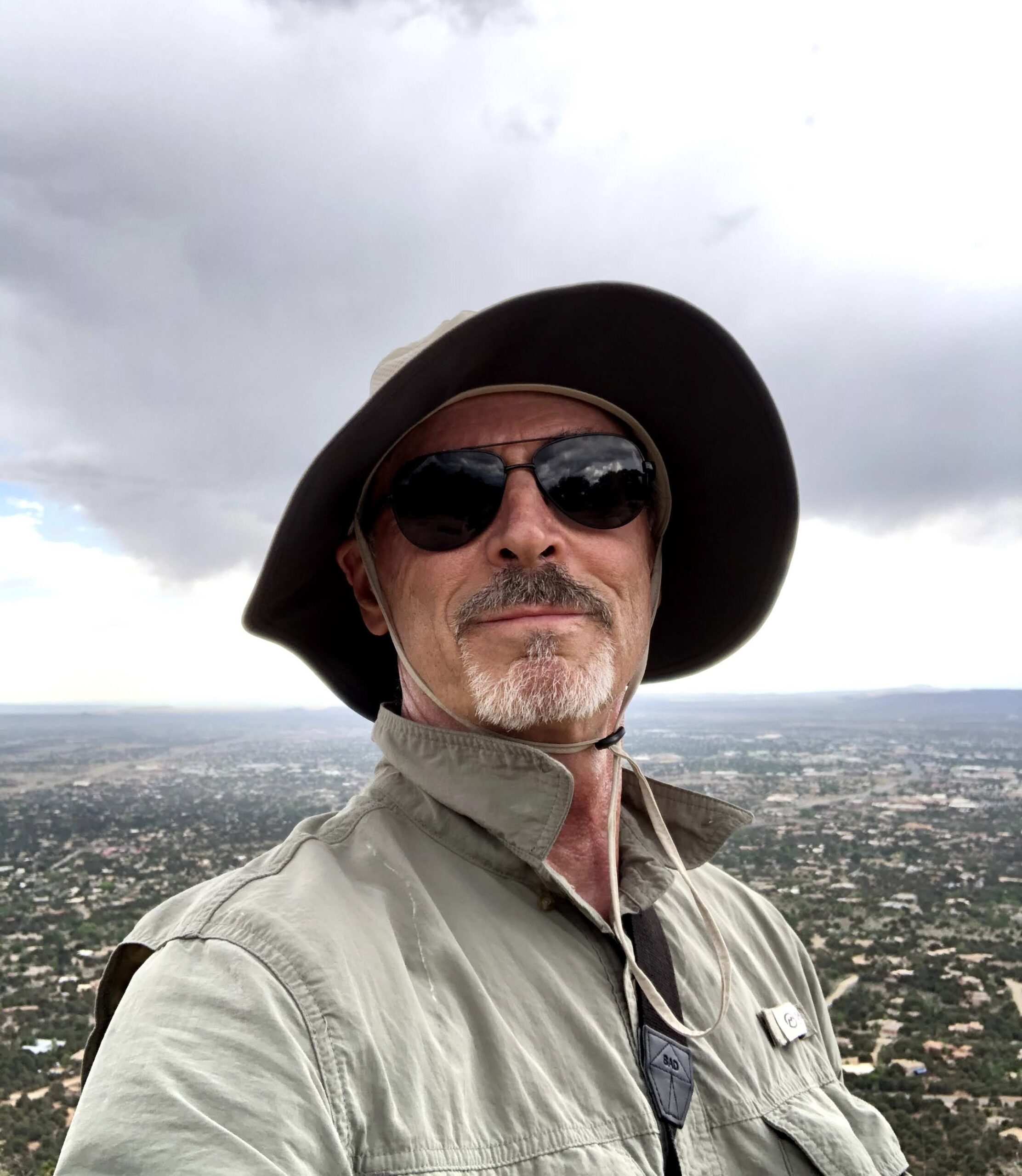

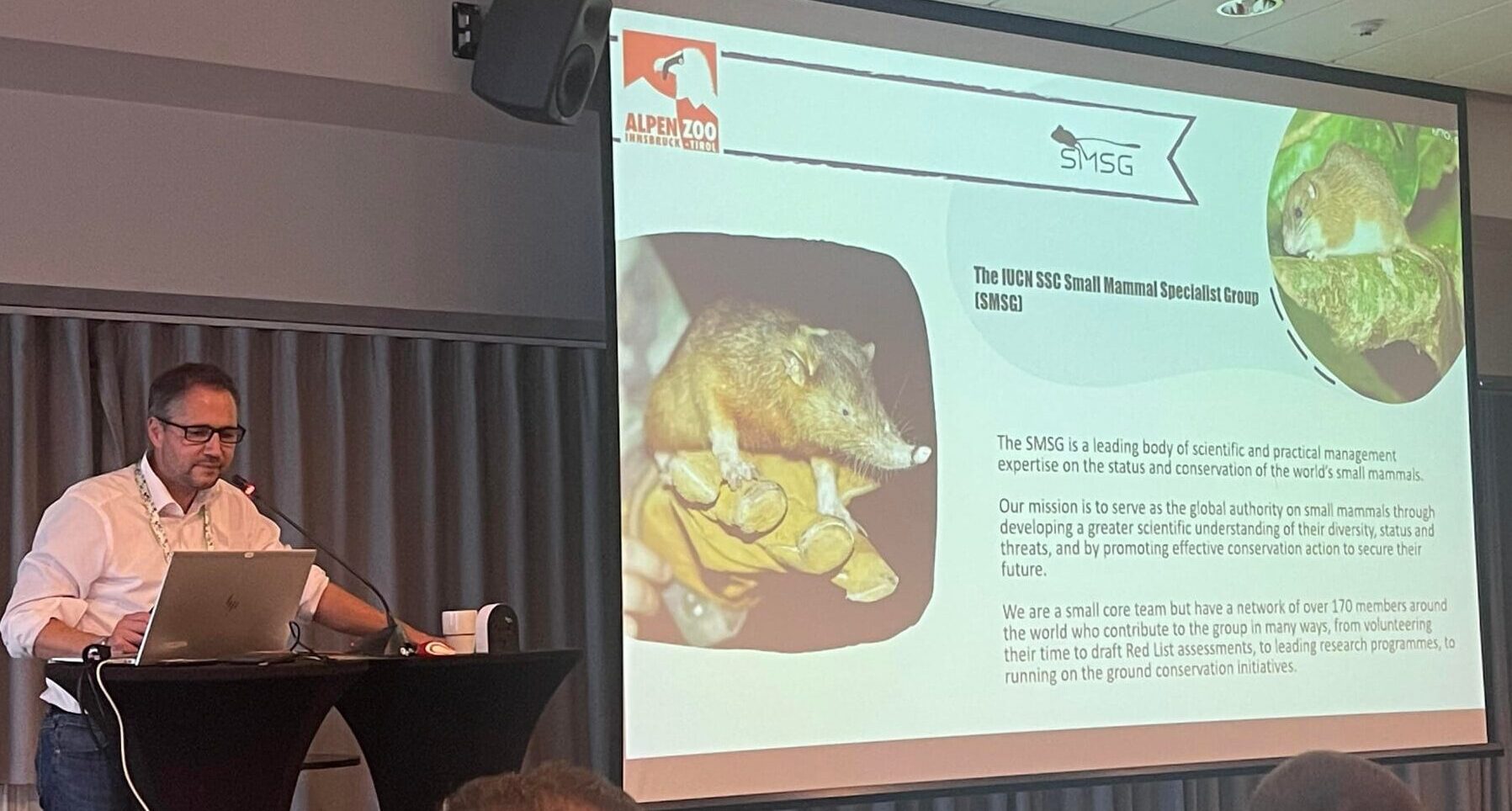

This month, after 13 years in the role, Tom is stepping down as the Co-Chair of the IUCN SSC Small Mammal Specialist Group (SMSG). Here we look at some of the huge contributions and achievements Tom has made to the group over this period.

Tom replaced Don Wilson as the co-chair of the newly formed SMSG back in 2012, with his focus on developing small mammal work across the Americas. He served as co-chair first with Rich Young and more recently with Ros Kennerley. During his time as Co-Chair, Tom was a professor at Texas A&M University (TAMU), until his retirement a few years ago. Through academic connections and teams of students at TAMU, he oversaw the previous Global Mammal Assessment for the Americas.

Tom replaced Don Wilson as the co-chair of the newly formed SMSG back in 2012, with his focus on developing small mammal work across the Americas. He served as co-chair first with Rich Young and more recently with Ros Kennerley. During his time as Co-Chair, Tom was a professor at Texas A&M University (TAMU), until his retirement a few years ago. Through academic connections and teams of students at TAMU, he oversaw the previous Global Mammal Assessment for the Americas.

Since his retirement from TAMU, Tom has been able to assist in the renewal of the Red List Partnership between TAMU and the SSC and promoted strong continued interest in the SMSG as well as assessment activities more widely, among faculty, staff, and administrators. The university has also renewed an agreement that Tom had previously negotiated with Re:wild to enhance capacity for both Red List and Green Status assessments.

In addition to his work for the SMSG, Tom has had many other engagements with the wider SSC activities. He first became engaged with the SSC when he was Executive Director of the Center for Applied Biodiversity Science at Conservation International in the early 2000s. He helped organise the funding of both the SSC Chair position (at the time Holly Dublin) as well as the first GMA (then under Simon Stuart) – so it has been nearly a quarter century of engagement! Tom also served on the Red List Committee from 2010 to 2023.

Some of Tom’s SMSG highlights:

- The development of a species action plan for the Santa Catarina Guinea Pig (Cavia intermedia) in 2019; the action plan is available in Portuguese here

- The creation of teams of Masters, PhD graduate students and undergraduates to conduct and complete the 2016 GMA for New World species

- SMSG Mexico regional action planning workshop in 2018

- Promoting small mammal research in the Conservation Biology publication “Support for rodent ecology and conservation to advance zoonotic disease research”

- Co-edited Volumes 6 and 7 of the Handbook of Mammals of the World, covering all rodents

- IUCN SSC Red List Training workshop in Brazil for about 30 people

- Organized and presented a workshop on Red List Assessments and the Brazilian Congress of Mammalogy in 2024

- Received the Aldo Leopold Award for Mammal Conservation from the American Society of Mammalogists in 2021

(c) Environment Agency – Abu Dhabi (EAD)

Tom says:

“I have greatly enjoyed and have been enriched by my work with the SMSG and the SSC. I am interested in continuing to support the SMSG in a more informal way by assisting in South America, helping move the assessments forward, supporting colleagues there to develop and submit proposals, and providing guidance to teams wishing to develop planning and action activities related to the SSC’s ASSESS-PLAN-ACT cycle.”

Hear from the SSC Chair, and some of our SMSG members, below.

-Dr Jon Paul Rodríguez, IUCN SSC Chair

“This is a bittersweet moment, as Tom has been a major force in this group and SSC in general, so it makes me sad to see him go. But Tom steps down as someone that had great success and left a fantastic group to continue with this work. You leave a substantial legacy.

Many thanks, Tom, for all that you have done for SSC. I look forward to remaining in touch and learning about your continued contributions, as I am certain that they will be great, too.”

-Professor Ricardo Ojeda, SMSG member

“I have known Tom since our days as a graduate student at the University of Pittsburgh, back in the late 1970s. Since then, we have maintained contact at different conferences and exchanged frequently on various topics related to the distribution, ecology, and conservation of Neotropical mammals.

My impression of Tom is that of an exceptional biologist with deep knowledge in various fields of mammalian biology. The diversity of topics developed in his scientific contributions is proof of this.

For several years Tom has been driving the appropriate means and space to translate much of his knowledge from basic research into the promotion of policies and strategies for the management of mammalian biodiversity conservation, particularly small mammals.

I particularly highlight his interest in promoting research related to small mammal species with knowledge gaps regarding their distribution, ranges of occupancy, abundance, and their relationship with protected area systems.

His departure from the IUCN SSC Small Mammal Specialist Group leaves an important foundation on which to continue diversifying and consolidating the path toward a more robust biodiversity conservation biology.

Of course, several of us understand that stepping down as Co-chair does not mean Tom is retiring from the small mammal research community and his pertinent and always sought-after expert opinion…

Cheers, Tom, and a good life, my friend!”

-Professor Jaime E. Jiménez, SMSG member

“I have been impressed by Tom’s generosity and grit – over so many years – to care about threatened species and to fight on how to protect them.”

-Professor Ella Vázquez-Domínguez, SMSG member

“Tom’s charm and enthusiastic leadership made the Small Mammals assessment in Puebla, México, one of the most enjoyable and fulfilling workshops I have ever participated in.”

Thank you for all of your work over the years Tom, from all of us in the SMSG team.

Joining this team is immensely exciting for me as it presents a chance to delve into the process of conducting assessments firsthand. It’s the perfect opportunity to apply the new framework I’ve learned about, which aims to quantify measures of species recovery and conservation success. As an early career conservation biologist, I’m particularly drawn to the Green Status’s focus on understanding how past conservation efforts have impacted species recovery and how current and future actions can contribute to their conservation with a comprehensive and ecologically functional approach. This opportunity will also give me the chance to interact with species specialists and learn about their conservation work on new species for me, which is really exciting!

Joining this team is immensely exciting for me as it presents a chance to delve into the process of conducting assessments firsthand. It’s the perfect opportunity to apply the new framework I’ve learned about, which aims to quantify measures of species recovery and conservation success. As an early career conservation biologist, I’m particularly drawn to the Green Status’s focus on understanding how past conservation efforts have impacted species recovery and how current and future actions can contribute to their conservation with a comprehensive and ecologically functional approach. This opportunity will also give me the chance to interact with species specialists and learn about their conservation work on new species for me, which is really exciting!

Recent Comments