The 12-week programme. Open to early-career conservationists, or graduate- or postgraduate-level conservationists working towards employment in the sector, DESMAN equips participants with a broad range of practical skills, knowledge and connections.

The 12-week programme. Open to early-career conservationists, or graduate- or postgraduate-level conservationists working towards employment in the sector, DESMAN equips participants with a broad range of practical skills, knowledge and connections.

Earlier this year, the SMSG supported one of our members – Rifa Nanziba – with her application to the DESMAN course. Rifa had not-long completed her MSc degree in Environment Management during which she focused on human-squirrel conflict in rural areas of Naogaon, Bangladesh. We were thrilled when Rifa’s DESMAN application was successful and, even further, when she was granted a full scholarship to the course. From September-December, she stayed at the Durrell Conservation Academy in Jersey (Channel Islands) for her studies. Here’s what Rifa has to say about it:

“Attending the DESMAN course at the Durrell Conservation Academy, validated by the University of Kent, was a life-changing experience for me. It opened new doors and felt like a dream come true. I am grateful for the support and recommendations from IUCN SSC SMSG Co-chair Dr Ros Kennerley, Programme Officer Dr Abi Gazzard, and my mentor, Muntasir Akash.

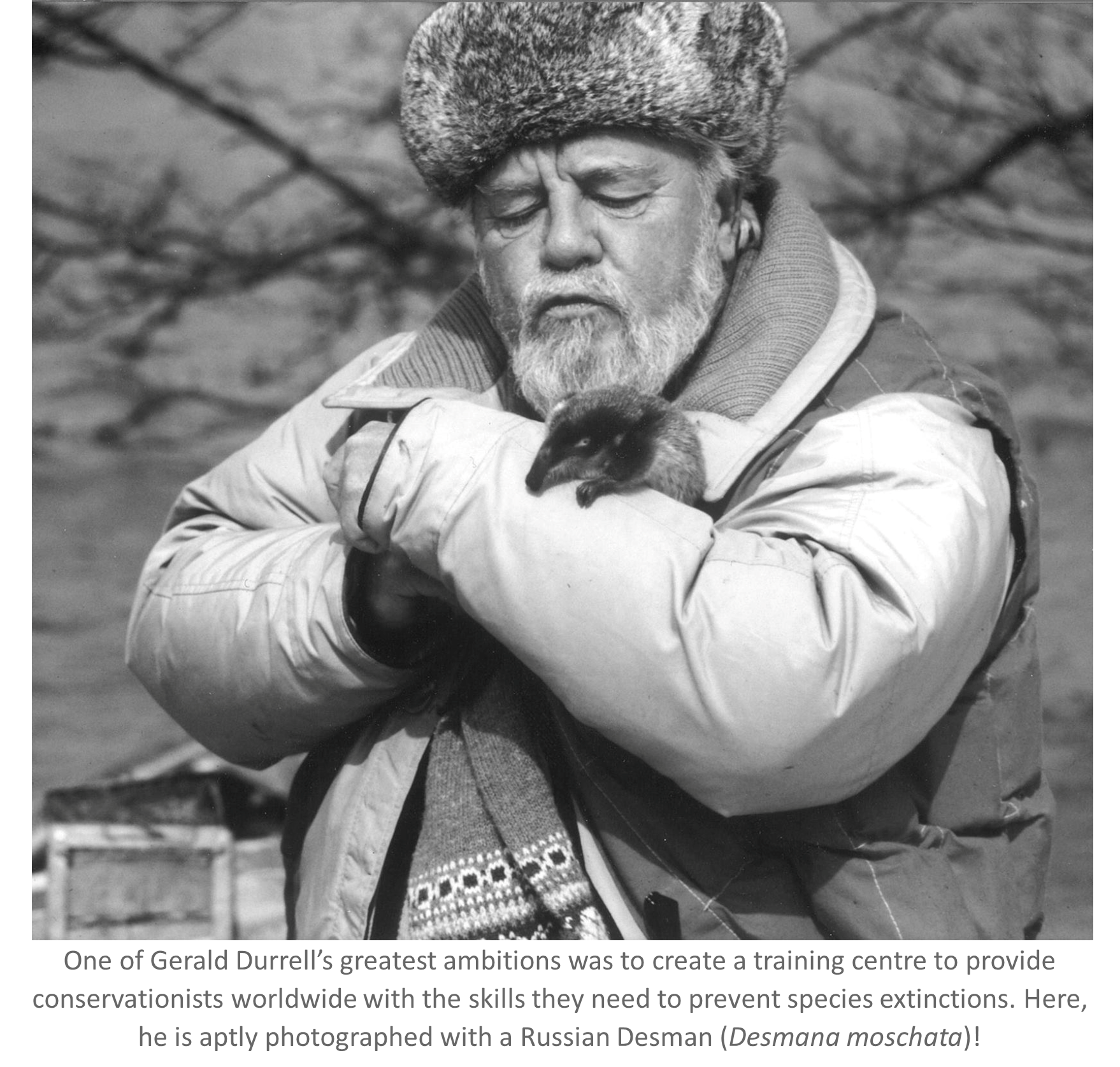

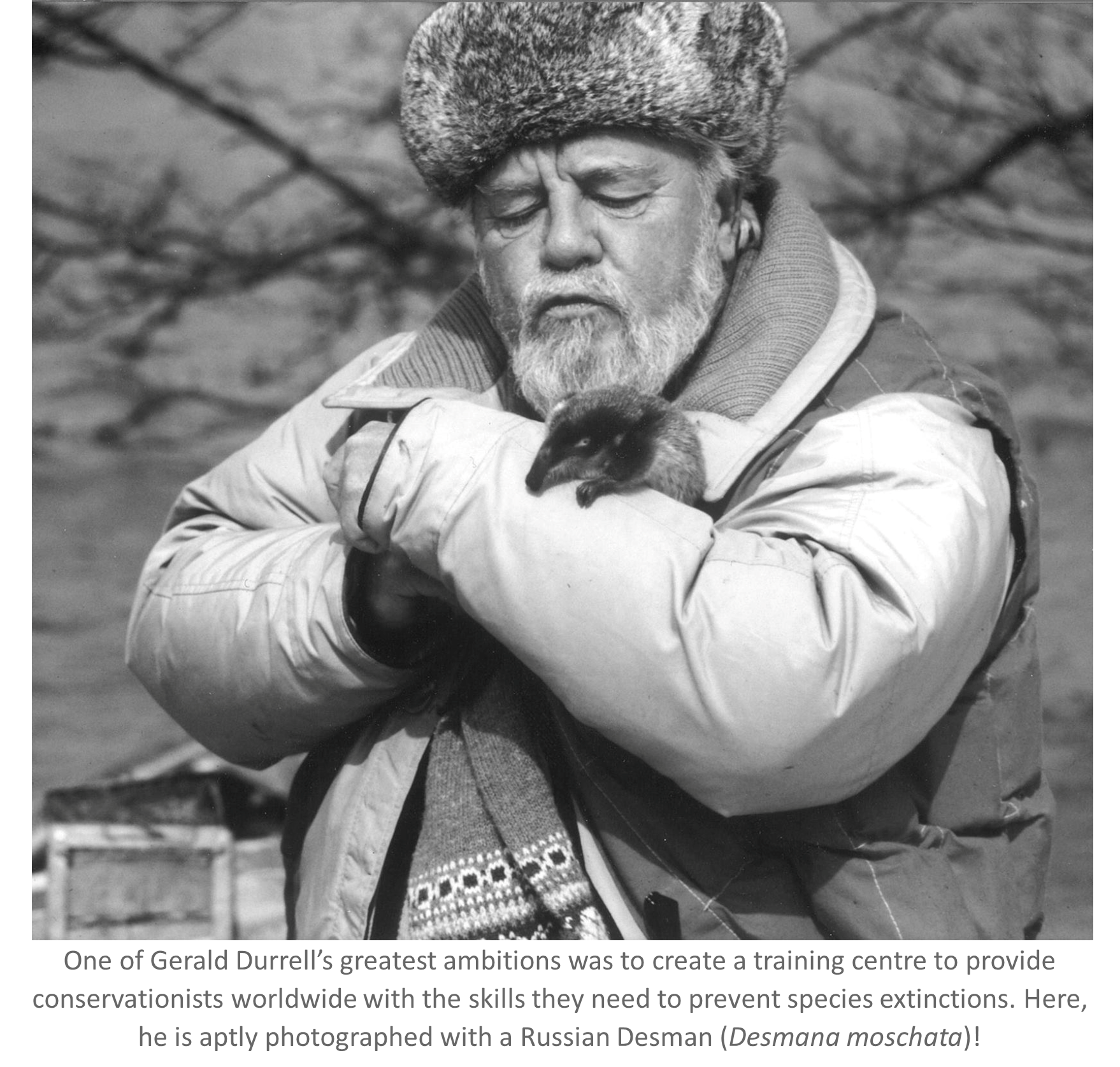

I found myself drawn to the teachings of DESMAN, a course crafted to set up conservationists with a diverse array of skills, enabling them to achieve peak efficacy in managing and participating in conservation projects. Under the tutelage of the renowned scientist Carl Jones, I was initiated into the intricacies of Species and Population Management. The course imparted valuable knowledge in statistics, IUCN Red List assessments, GIS, project planning and management, research methods, and survey techniques such as camera trapping, radio telemetry, and the use of drones. Additionally, we explored topics such as human-wildlife conflict, community conservation and livelihoods, budgeting, and grant proposal writing. I had an amazing chance to meet Lee Durrell and hear about her and Gerald Durrell’s incredible conservation work and projects around the world, along with how the famous Jersey Zoo and Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust were established.

What set DESMAN apart was the emphasis on practical work, complementing the theoretical lectures. As part of this, I was privileged to shadow mammal keepers for four days in Jersey Zoo, honing my mammal husbandry skills, helping me to realise that I might want to be a wildlife rehabilitator too as in my country there are not many rehabilitation centres. Furthermore, I had the opportunity to connect with a vast network of wildlife enthusiasts through Durrell, who remain eager to support me in my future endeavours. Besides all the study and technical experience, I had a blast in Jersey as the local volunteers were kind enough to take us to many beautiful and historical places on the island. As well as that, I gained a group of fellow DESMAN participants as my friends who, after staying with each other for a whole 3 months, are without any doubt also part of my knowledge, experience and networking.

After completing the DESMAN course, I feel confident in my ability to work in wildlife conservation, specifically with small mammals in Bangladesh. I am excited to apply my new knowledge and skills in this field.”

Rifa’s final assessment was a hypothetical project proposal. She chose to write a proposal to questionnaire-survey the Santal community of Naogaon on the drivers and impacts of small mammal hunting and consumption – very little is currently known about the use of small mammals in this region. We look forward to seeing what Rifa gets up to next!

If you are a small mammal researcher interested in furthering your skills through Durrell’s DESMAN course, or may know of suitable participants, please get in touch. Places are limited. You can find more information about the syllabus here and scholarships here.

By Rifa Nanziba and Abi Gazzard

Joining this team is immensely exciting for me as it presents a chance to delve into the process of conducting assessments firsthand. It’s the perfect opportunity to apply the new framework I’ve learned about, which aims to quantify measures of species recovery and conservation success. As an early career conservation biologist, I’m particularly drawn to the Green Status’s focus on understanding how past conservation efforts have impacted species recovery and how current and future actions can contribute to their conservation with a comprehensive and ecologically functional approach. This opportunity will also give me the chance to interact with species specialists and learn about their conservation work on new species for me, which is really exciting!

Joining this team is immensely exciting for me as it presents a chance to delve into the process of conducting assessments firsthand. It’s the perfect opportunity to apply the new framework I’ve learned about, which aims to quantify measures of species recovery and conservation success. As an early career conservation biologist, I’m particularly drawn to the Green Status’s focus on understanding how past conservation efforts have impacted species recovery and how current and future actions can contribute to their conservation with a comprehensive and ecologically functional approach. This opportunity will also give me the chance to interact with species specialists and learn about their conservation work on new species for me, which is really exciting!

The findings

The findings

Recent Comments