The Malagasy Giant Jumping Rat – endemic to Madagascar – has been under pressure from habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation for years. Now, in the latest IUCN Red List update, this species has been moved to a higher threat category, from Endangered to Critically Endangered.

The Malagasy Giant Jumping Rat is the only living species in the ‘jumping rat’ genus Hypogeomys. As its name suggests, this forest-dwelling rodent has an impressive jumping ability. Its disproportionately large back feet help it to spring almost one metre into the air when evading predators. Such rabbit-like quirks of the jumping rat can also be seen in its nesting behaviour; during the day, it rests in an underground burrow complex. At night, it becomes active to forage for fallen fruit, leaves and seeds. The burrows of the Malagasy giant jumping rat are relatively high maintenance with entrances that are excavated and re-sealed every time a rat leaves and returns. Rather unusually, this rodent lives in its burrows in social monogamy: a male and female pair will remain together until one mate dies.

The Malagasy Giant Jumping Rat is the only living species in the ‘jumping rat’ genus Hypogeomys. As its name suggests, this forest-dwelling rodent has an impressive jumping ability. Its disproportionately large back feet help it to spring almost one metre into the air when evading predators. Such rabbit-like quirks of the jumping rat can also be seen in its nesting behaviour; during the day, it rests in an underground burrow complex. At night, it becomes active to forage for fallen fruit, leaves and seeds. The burrows of the Malagasy giant jumping rat are relatively high maintenance with entrances that are excavated and re-sealed every time a rat leaves and returns. Rather unusually, this rodent lives in its burrows in social monogamy: a male and female pair will remain together until one mate dies.

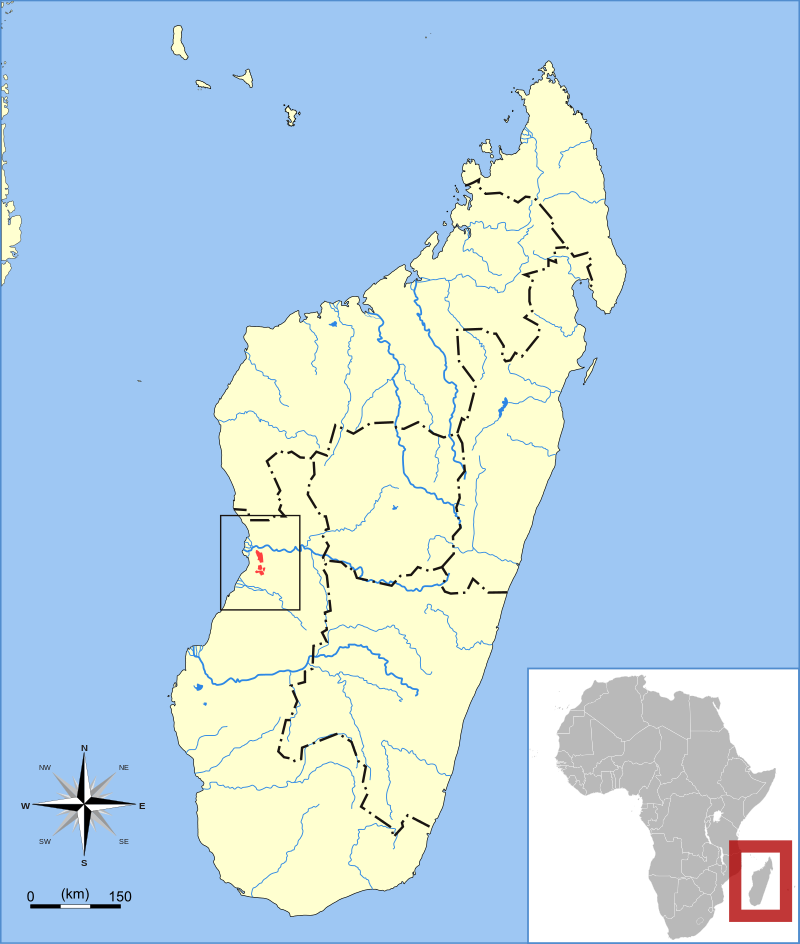

Today, this unique species is found in only two isolated fragments of the Menabe region on the west coast of Madagascar, occupying a total area of less than 200km2. Fossil evidence indicates that a millennium ago the range of the Malagasy giant jumping rat would have extended much further south.

Substantial habitat loss across this species’ historical range has been the result of climate-related aridification as well as human activities. Slash and burn agriculture, logging, charcoal production and illegal maize and peanut production have all contributed to unprecedented rates of deforestation in the now protected Menabe Antimena area: by 2014, approximately 4,000 hectares of forest was being lost per year.

Habitat loss is not the only threat the giant jumping rat faces. It may be susceptible to hantaviruses recently detected in other rodents in Madagascar, as well as the negative impacts of feral cats and dogs which pose a risk as predators as well as carriers of disease.

Habitat loss is not the only threat the giant jumping rat faces. It may be susceptible to hantaviruses recently detected in other rodents in Madagascar, as well as the negative impacts of feral cats and dogs which pose a risk as predators as well as carriers of disease.

These challenges have driven a severe and ongoing drop in numbers of the giant jumping rat. Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust undertook urgent survey work in the field in 2019 (even capturing rare footage of the rodents) and, based on the results of such surveys, the population was estimated to have declined by 88% between the years 2007-2019. In the northern fragment of its range, this decline reached 92% over the same period. Approximately just 5,000 individuals remain and the alarming reduction in numbers is what qualifies the Malagasy Giant Jumping Rat for Critically Endangered status.

Can the Malagasy giant jumping rat bounce back from the brink of extinction?

This rodent has a slow reproductive strategy. Only one or two young are produced per litter and sexual maturity of females is likely not reached until after two years. Its low reproductive output in combination with rapid habitat destruction and other fast-acting threats highlights the urgency of conservation efforts for this species.

In captivity, conservation action for the giant jumping rat has been ongoing since the 1990s when Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust established the first ‘safety net’ population in Jersey Zoo. In the wild, the forest in which the jumping rat resides was granted statutory protection in 2006, though this has not alleviated the significant threat of illegal deforestation.

There is now a need to focus efforts on stricter habitat protection measures, investigate the potential pathogens threatening this species, control feral dogs and cats and, ideally, establish a comprehensive action plan for saving the species. Without any intensive conservation intervention or habitat security, the Malagasy Giant Jumping Rat could disappear forever.

Author: Abi Gazzard (SMSG Programme Officer)

The IUCN SSC Small Mammal Specialist Group is delighted to welcome Abi as the new SMSG Programme Officer. Abi joined the team in May 2022 and will be based at Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. Her role will involve working alongside the team to deliver Red List assessments and other key activities. Abi’s interest in small mammals grew from her MSc project, in which she conducted an occupancy study of the West European hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus) using footprint tracking tunnels in the UK. She then went on to complete a PhD at the University of Reading in 2022 again focusing on West European hedgehogs, but specifically in urban areas. Her research incorporated a range of methodological approaches, such as radio tracking and citizen science surveys, to study conservation actions and hedgehog activity primarily in residential gardens. Beyond hedgehogs, Abi has previously worked on projects with wildlife researchers in Malaysia and Europe. She hopes to continue expanding her knowledge of, and contributing to the conservation of, Eulipotyphlans and other small mammals.

The IUCN SSC Small Mammal Specialist Group is delighted to welcome Abi as the new SMSG Programme Officer. Abi joined the team in May 2022 and will be based at Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. Her role will involve working alongside the team to deliver Red List assessments and other key activities. Abi’s interest in small mammals grew from her MSc project, in which she conducted an occupancy study of the West European hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus) using footprint tracking tunnels in the UK. She then went on to complete a PhD at the University of Reading in 2022 again focusing on West European hedgehogs, but specifically in urban areas. Her research incorporated a range of methodological approaches, such as radio tracking and citizen science surveys, to study conservation actions and hedgehog activity primarily in residential gardens. Beyond hedgehogs, Abi has previously worked on projects with wildlife researchers in Malaysia and Europe. She hopes to continue expanding her knowledge of, and contributing to the conservation of, Eulipotyphlans and other small mammals.

My six month internship at Durrell Wildlife Trust and the IUCN SSC Small Mammal Specialist Group has been an exciting and fulfilling adventure. Despite having spent the majority of my time working remotely, the distance felt much shorter with a team that made me feel very much welcomed. I looked forward to our Durrell weekly Monday catch up sessions, always getting inspired by the exciting fieldwork my other colleagues have planned. Coming directly into the internship from my academic studies, this internship was great exposure to the working world of conservation. As my tasks were wide-ranged, I was able to experience what it was like to work in multiple dimensions of conservation and decide whether I enjoyed it. I not only acquired more knowledge of small mammals and their ecology, but I also further sharpened my research and writing abilities. From writing my first press release for the conservation status change of the Pyrenean Desman, to amending Red List accounts on the water vole and Sinharaja shrew, to submitting an article on the Southeast Asian rodent meat trade for publication, these tasks honed my ability to be an independent researcher. One of the perks of working in a reputable organisation such as this one is the connections I have made, especially with TRAFFIC and Wildlife Conservation Society. These connections will no doubt be useful in the future as I continue my journey as a conservation scientist. Finally, I would like to personally thank my supervisor, Ros, for her guidance and support throughout my internship, and for overall making my experience more pleasant and enjoyable.

My six month internship at Durrell Wildlife Trust and the IUCN SSC Small Mammal Specialist Group has been an exciting and fulfilling adventure. Despite having spent the majority of my time working remotely, the distance felt much shorter with a team that made me feel very much welcomed. I looked forward to our Durrell weekly Monday catch up sessions, always getting inspired by the exciting fieldwork my other colleagues have planned. Coming directly into the internship from my academic studies, this internship was great exposure to the working world of conservation. As my tasks were wide-ranged, I was able to experience what it was like to work in multiple dimensions of conservation and decide whether I enjoyed it. I not only acquired more knowledge of small mammals and their ecology, but I also further sharpened my research and writing abilities. From writing my first press release for the conservation status change of the Pyrenean Desman, to amending Red List accounts on the water vole and Sinharaja shrew, to submitting an article on the Southeast Asian rodent meat trade for publication, these tasks honed my ability to be an independent researcher. One of the perks of working in a reputable organisation such as this one is the connections I have made, especially with TRAFFIC and Wildlife Conservation Society. These connections will no doubt be useful in the future as I continue my journey as a conservation scientist. Finally, I would like to personally thank my supervisor, Ros, for her guidance and support throughout my internship, and for overall making my experience more pleasant and enjoyable.

The Togo Mouse (Leimacomys buettneri) was last seen in 1890 when it was first collected about 20 km east of Kyabobo Range National Park (KRNP) near the border between Ghana and Togo. Until now, there has been limited effort to locate the species using suitable trapping methodologies, but staff from KRNP believe they know the species and refer to it locally as “Yefuli”, thus hope remains that the species may have survived within the forests of West Africa.

The Togo Mouse (Leimacomys buettneri) was last seen in 1890 when it was first collected about 20 km east of Kyabobo Range National Park (KRNP) near the border between Ghana and Togo. Until now, there has been limited effort to locate the species using suitable trapping methodologies, but staff from KRNP believe they know the species and refer to it locally as “Yefuli”, thus hope remains that the species may have survived within the forests of West Africa.  The Dwarf Hutia (Mesocapromys nanus) is a guinea pig-like rodent from Cuba, last collected in 1951. They are believed to build small platforms with holes as refuges in the dry islets and forest outcrops in the Zapata Swamp. Possible evidence of a nest and some suspicious scat was located in 1978, but continued efforts in this largely inaccessible swampy region are needed to confirm the status of the species.

The Dwarf Hutia (Mesocapromys nanus) is a guinea pig-like rodent from Cuba, last collected in 1951. They are believed to build small platforms with holes as refuges in the dry islets and forest outcrops in the Zapata Swamp. Possible evidence of a nest and some suspicious scat was located in 1978, but continued efforts in this largely inaccessible swampy region are needed to confirm the status of the species.

Author: Erika Lau

Author: Erika Lau

Additional funding secured

Additional funding secured

Recent Comments